-

Study

-

Quick Links

- Open Days & Events

- Real-World Learning

- Unlock Your Potential

- Tuition Fees, Funding & Scholarships

- Real World Learning

-

Undergraduate

- Application Guides

- UCAS Exhibitions

- Extended Degrees

- School & College Outreach

- Information for Parents

-

Postgraduate

- Application Guide

- Postgraduate Research Degrees

- Flexible Learning

- Change Direction

- Register your Interest

-

Student Life

- Students' Union

- The Hub - Student Blog

- Accommodation

- Northumbria Sport

- Support for Students

-

Learning Experience

- Real-World Learning

- Research-enriched learning

- Graduate Futures

- The Business Clinic

- Study Abroad

-

-

International

International

Northumbria’s global footprint touches every continent across the world, through our global partnerships across 17 institutions in 10 countries, to our 277,000 strong alumni community and 150 recruitment partners – we prepare our students for the challenges of tomorrow. Discover more about how to join Northumbria’s global family or our partnerships.

View our Global Footprint-

International Students

- Information for International Students

- Northumbria and your Country

- International Student Events

- Application Guide

- Entry Requirements and Education Country Agents

- Global Offices and Regional Teams

- English Requirements

- English Language Centre

- International student support

- Cost of Living

-

International Fees and Funding

- International Undergraduate Fees

- International Undergraduate Funding

- International Masters Fees

- International Masters Funding

- International Postgraduate Research Fees

- International Postgraduate Research Funding

- Useful Financial Information

-

International Partners

- Agent and Representatives Network

- Global Partnerships

- Global Community

-

International Mobility

- Study Abroad

- Information for Incoming Exchange Students

-

-

Business

Business

The world is changing faster than ever before. The future is there to be won by organisations who find ways to turn today's possibilities into tomorrows competitive edge. In a connected world, collaboration can be the key to success.

More on our Business Services-

Business Quick Links

- Contact Us

- Business Events

- Research and Consultancy

- Education and Training

- Workforce Development Courses

- Join our mailing list

-

Education and Training

- Higher and Degree Apprenticeships

- Continuing Professional Development

- Apprenticeship Fees & Funding

- Apprenticeship FAQs

- How to Develop an Apprentice

- Apprenticeship Vacancies

- Enquire Now

-

Research and Consultancy

- Space

- Energy

- AI Futures

- CHASE: Centre for Health and Social Equity

- NESST

-

-

Research

Research

Northumbria is a research-rich, business-focused, professional university with a global reputation for academic quality. We conduct ground-breaking research that is responsive to the science & technology, health & well being, economic and social and arts & cultural needs for the communities

Discover more about our Research-

Quick Links

- Research Peaks of Excellence

- Academic Departments

- Research Staff

- Postgraduate Research Studentships

- Research Events

-

Research at Northumbria

- Interdisciplinary Research Themes

- Research Impact

- REF

- Partners and Collaborators

-

Support for Researchers

- Research and Innovation Services Staff

- Researcher Development and Training

- Ethics, Integrity, and Trusted Research

- University Library

- Vice Chancellors Fellows

-

Research Degrees

- Postgraduate Research Overview

- Doctoral Training Partnerships and Centres

- Academic Departments

-

Research Culture

- Research Culture

- Research Culture Action Plan

- Concordats and Commitments

-

-

About Us

-

About Northumbria

- Our Strategy

- Our Staff

- Our Schools

- Place and Partnerships

- Leadership & Governance

- University Services

- Northumbria History

- Contact us

- Online Shop

-

-

Alumni

Alumni

Northumbria University is renowned for the calibre of its business-ready graduates. Our alumni network has over 253,000 graduates based in 178 countries worldwide in a range of sectors, our alumni are making a real impact on the world.

Our Alumni - Work For Us

Katy Jenkins, Associate Professor of International Development and Co-Director of the Centre for International Development at Northumbria University, writes in Discover Society about her sociological photography project.

“We’re always saying ‘No, no, no to mining’, but we never put forward an alternative or positive proposal.” This was how one woman explained her motivation to take part in my participatory photography project, which explores women anti-mining activists’ conceptions of ‘Development’, in the context of living with proposed and actual large-scale resource extraction.

The project, funded by a Leverhulme Trust Fellowship, involves working with a group of 12 women from Cajamarca, a small city in the North of Peru, enabling them to use photography to reflect on and capture their own ways of thinking about Development, and in particular to think through alternative visions of Development that challenge the dominant Peruvian national narrative of extractive-led Development.

(Right: Gladis Chilon Gutierrez/Women, Mining and Photography Project 2017)

Yanacocha gold mine, the largest gold mine in Latin America, is owned by US Newmont Mining Corporation, Peruvian Minas Buenaventura and the World Bank’s International Financial Corporation. It has operated in the region of Cajamarca since 1993. During this time, there has been widespread and growing concern about the mine’s operation and, in particular, its environmental impact, especially in relation water quality and quantity. The city of Cajamarca has become an emblematic site in relation to socio-environmental conflicts around mining.

In 2000, local opposition to mining intensified, and gained international prominence, when a truck contracted by the mine spilt significant quantities of mercury along a stretch of road in and around community of Choropampa, with devastating health and environmental impacts. Then in the mid-2000s, protests erupted in opposition to the company’s proposed Cerro Quilish expansion, which sought to develop the Quilish mountain, which is considered a sacred place by local people, has a fragile ecosystem and is situated at the head of the watershed. The strength of community opposition and public opinion eventually forced the Minera Yanacocha company to withdraw from the Quilish concession but only after violent confrontations between protestors and the police.

Most recently, Cajamarca has been in the spotlight for vehement and prolonged opposition to the proposed Minas Conga project, a proposed multi-billion dollar expansion to Yanacocha’s existing project. Community opposition in both Cajamarca city and the wider region of Cajamarca, culminated in protests during 2011 and 2012, leaving five protestors dead, and eventually leading to the indefinite suspension of the project. Nevertheless, despite the suspension of Conga, there are ongoing tensions around actual and proposed extractive activities, personified in the now iconic figure of Máxima Acuña Chaupe – winner of the 2016 Goldman Environmental Prize – and her battle against Newmont Mining Corporation. Activist organisations continue to fiercely resist Conga and other possible new mining developments, as well as opposing the broader development model associated with this sort of large-scale resource extraction.

(Right: 2 Felicita Vasquez Huaman/Women, Mining and Photography Project 2017)

The region of Cajamarca has thus become internationally renowned for its opposition to large-scale mining and, over the years, there has been a steady stream of journalists, academics, PhD students, filmmakers and photographers, supporting the Cajamarquinos in their struggle and sharing it with the world. Whilst this has given international prominence to Cajamarca’s struggles, activists, such as the women those involved in this particular project, do feel quite thoroughly ‘researched’ and tend to have a well-rehearsed ‘script’ in relation to recounting their involvement in the conflict. The women activists embraced this project as an opportunity to construct and disseminate their own narratives, and to create a set of resources to enable them to actively communicate their ideas and perspectives in a distinctive way. Participatory photography provides a tool with which to achieve this, facilitating a move away from more traditional interviewer/interviewee power dynamics, and allowing participants to set the agenda and foreground the topics they deem important.

Over three months during 2017, a group of women drawn from three women’s organisations (two from Cajamarca city, and one from Celendin (a small town close to the proposed Conga development)), took part in a series of workshops and activities aimed at capturing their distinct approaches to contesting mining developments, and thinking about alternatives, using the medium of participatory photography. In the course of the project, the women took several thousand photos, reflecting on three themes they chose to work on – ‘alternatives to resource extraction’, ‘wellbeing’ and ‘community’. These were themes that the women themselves thought it important to explore, and that reflected discussions about the meaning of ‘Development’ from the initial participatory workshop.

(Right: Filomila Sangay Lopez/Women, Mining and Photography Project 2017)

Drawing on their own lives and experiences, the women’s photos provide an optimistic, vibrant and rich perspective on the region of Cajamarca and their hopes for its future. Participatory photography is often used with marginalised and disadvantaged groups, and provides an opportunity for alternative voices and perspectives to come to the fore. Many of the women participants in this project had never used a camera before. For them, the most important aspect of the project is the opportunity to exhibit their work in the main plaza in Cajamarca city, enabling them and their ideas to occupy and claim (increasingly restricted) civic space, and to showcase their newly acquired skills, their creativity and visions for the future, to local people, government officials, the mining company, and organisations involved in contesting mining. This exhibition is planned for International Women’s Day, 8th March 2018.

The women’s photos reflect the importance they place on a more people-centred, human-scale Development, a strong contrast with the highly industrialised and mechanised forms of mining that they experience in their region, and strongly contest. A sense of hope permeates the women’s images, foregrounding that which they value as distinctive and meaningful, and portraying Cajamarca as a culturally, historically and naturally rich region with an abundance of resources and opportunities.

Such images and perspectives stand in stark contrast to the devastation and destruction wrought by large scale mining in the region, and across the global South. In choosing not to focus on this aspect of mining, the project aimed to open up spaces of possibility rather than capturing the already well-documented and extensive negative impacts of mining – which might also have placed the women activists in difficult or dangerous situations, and exposed them to multiple risks.

The women’s own subjectivities and positionalities as anti-mining activists have been central in the types of image they have generated. Indeed, this is an integral expectation of participant photography; there is no expectation of, or desire for, objective or values-free ‘data’. In this case, aspects characteristic of much of the campaigning narratives of the broader anti-mining movement are central to the visions put forward in the women’s photos. Food and culture, exemplifying a threatened rural way of life, were recurring themes that appeared in all twelve women’s photos, despite most of the women currently living in the city.

Many of the women had grown up in rural communities, and some self-identified as indigenous women (still relatively uncommon in much of Peru due to the continuing legacy of severe discrimination against indigenous peoples). Many women had purposely sought out images of rurality and, in particular, agricultural abundance, and used these images to emphasise the opportunities they felt small-scale agriculture presented for an alternative model of Development, not based on mineral extraction.

(Right: Yeni Cojal Rojas/Women, Mining and Photography Project 2017)

It should be recognised that there is an element of rose-tinted spectacles to these sorts of images, they portray an idealised vision of rural life, and for the most part do not capture poverty and inequality within their purview. Despite this caveat, they do reflect on ideas around sustainability, and self-sustenance, attesting to the women’s belief that Development should not be something imposed from outside but should emerge from within a community and a particular context.

The women’s desire to portray themselves and other women as active agents of change within their communities is also evident in many of their photos. Their images capture examples of women as micro-entrepreneurs; reflect on opportunities for the diversification of women’s livelihoods (including herbal remedies, elaboration of dairy products, soap production); and show women in myriad roles, as agriculturalists, food producers, mothers, muralists, market sellers, musicians, community organisers and activists. They portray women as integral to the functioning and survival of communities and families, and as capable, self-motivated and hard-working individuals.

Most recently, having come to the end of the active photography phase of the project, I conducted interviews with the women about the photographs they have taken – giving them an opportunity to reflect upon what photos they took and why, and also what photos they chose not to take, or were unable to take. These interviews, as well as narratives and poems written by the women about some of their photos, will be analysed over the coming months, and will provide a deeper insight into the women’s stances, motivations and aspirations, prior to the final exhibition of a selection of the women’s images and narratives in spring 2018. The project can be followed here.

Katy Jenkins is Associate Professor of International Development and Co-Director of the Centre for International Development in the Department of Social Sciences, Northumbria University. Katy’s research focuses on women’s activism and community organising in Latin America, and she is currently involved in several projects exploring women’s resistance to large scale resource extraction.

News

- Telescope reveals surprising secrets in Jupiter's northern lights

- Working-class roots drive North East graduate’s AI healthcare revolution

- National Fellowship honours Northumbria nursing leader

- Venice Biennale Fellowship

- First cohort of Civil Engineering Degree Apprentices graduate from Northumbria

- Northumbria expands results day support for students

- Northumbria academic recognised in the British Forces in Business Awards 2025

- £1.2m grant extends research into the benefits of breast milk for premature babies

- Northumbria graduate entrepreneur takes the AI industry by storm

- Study identifies attitudes towards personal data processing for national security

- Lifetime Brands brings student design concept to life

- New study reveals Arabia’s ‘green past’ over the last 8 million years

- How evaluation can reform health and social care services

- Researchers embark on a project to further explore the experiences of children from military families

- Northumbria University's pioneering event series returns with insights on experiential and simulated learning

- Support for doctoral students to explore the experiences of women who have been in prison

- Funding boost to transform breastfeeding education and practice

- A new brand of coffee culture takes hold in the North East

- BBRSC awards £6m of funding for North East Bioscience Doctoral Students

- £3m funding to evaluate health and social care improvements

- Balfour Beatty apprentices graduate from Northumbria University

- Long COVID research team wins global award

- Northumbria researchers lead discussions at NIHR event on multiple and complex needs

- Healthcare training facility opens to support delivery of new T-level course

- Young people praise Northumbria University for delivery of HAF Plus pilot

- Nursing academics co-produce new play with Alphabetti Theatre

- Research project to explore the experiences of young people from military families

- Academy of Social Sciences welcomes two Northumbria Professors to its Fellowship

- Northumbria University set to host the Royal College of Nursings International Nursing Research Conference 2024

- 2.5m Award Funds Project To Encourage More People Into Health Research Careers

- Advice available for students ahead of A-level results day

- Teaching excellence recognised with two national awards

- Northumbria law student crowned first Apprentice of the Year for the region

- Northumbria University launches summer activities to support delivery of Holiday Activities and Food programme

- UK health leader receives honorary degree from Northumbria University

- Use of AI in diabetes education achieves national recognition

- Research animation explores first-hand experiences of receiving online support for eating disorders

- Careers event supports graduate employment opportunities

- Northumbria University announces £50m space skills, research and development centre set to transform the UK space industry

- The American Academy of Nursing honours Northumbria Professor with fellowship

- New report calls for more support for schools to improve health and wellbeing in children and young people

- AI experts explore the ethical use of video technology to support patients at risk of falls

- British Council Fellows selected from Northumbria University for Venice Biennale

- Prestigious nomination for Northumbria cyber security students

- Aspiring Architect wins prestigious industry awards

- Lottery funding announced to support mental health through creative education

- Early intervention can reduce food insecurity among military veterans

- Researching ethical review to support Responsible AI in Policing

- Northumbria named Best Design School at showcase New York Show

- North East universities working together

- Polar ice sheet melting records have toppled during the past decade

- Beyond Sustainability

- Brewing success: research reveals pandemic key learnings for future growth in craft beer industry

- City's universities among UK best

- Famous faces prepare to take to the stage to bring a research-based performance to life

- Insights into British and other immigrant sailors in the US Navy

- International appointment for law academic

- Lockdown hobby inspires award-winning business launch for Northumbria student

- Lasting tribute to Newcastle’s original feminist

- Outstanding service of Northumbria Professor recognised with international award

- Northumbria academics support teenagers to take the lead in wellbeing research

- Northumbria University becomes UK's first home of world-leading spectrometer

- Northumbria's Vice-Chancellor and Chief Executive to step down

- Out of this world experience for budding space scientists

- Northumbria engineering graduate named as one of the top 50 women in the industry

- Northumbria University signs up to sustainable fashion pledge

- Northumbria demonstrates commitment to mental health by joining Mental Health Charter Programme

- Virtual reality tool that helps people to assess household carbon emissions to go on display at COP26

- EXPERT COMMENT: Why thieves using e-scooters are targeting farms to steal £3,000 quad bikes, and what farmers can do to prevent it

- Exhibition of lecturer’s woodwork will help visitors reimagine Roman life along Hadrian’s Wall

- Students reimagine food economy at international Biodesign Challenge Summit

- Northumbria storms Blackboard Catalyst Awards

- Breaking news: Northumbria’s Spring/Summer Newspaper is here!

- UK’s first ever nursing degree apprentices graduate and join the frontline

- Massive decrease in fruit and vegetable intake reported by children receiving free school meals following lockdown

- Northumbria awards honorary degrees at University’s latest congregations

Latest News and Features

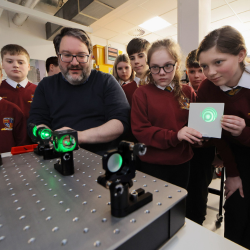

University partnership brings space research to life for school pupils

A North East school has partnered with solar and space physics experts from Northumbria University…

.png?modified=20250916102106)

Telescope reveals surprising secrets in Jupiter's northern lights

An international team of scientists, led by a PhD researcher from Northumbria University, has…

Northumbria Film graduates receive Royal Television Society honours

Two Northumbria University Film graduates have won Royal Television Society (RTS) Student Awards…

Scientists reveal the best and worst-case scenarios for a warming Antarctica

A new analysis of decades of research on the Antarctic Peninsula, involving experts from Northumbria…

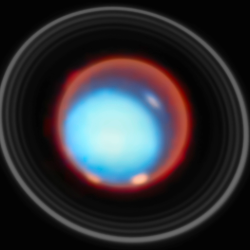

PhD student maps mysterious upper atmosphere of Uranus for the first time

A Northumbria University PhD student has led an international team of astronomers in creating…

Developing technology to help empower young innovators across the globe

Northumbria University researchers have joined forces with the International Federation of…

Working-class roots drive North East graduate’s AI healthcare revolution

A Northumbria University graduate has developed groundbreaking AI technology that could save…

Families back nationwide school holiday activities programme in record survey

A landmark survey of 20,000 parents and carers has revealed overwhelming support for the Government's…

Upcoming events

Launch of the Northern Interprofessional Education Strategy

Northumbria University

-

Broken Bonds: New Perspectives on Marital Breakdown

The Great Hall

-